Klang (Part One) – A Historical Royal Town

There was once a Sultan of Selangor who had a son. His son falls into debt from an investment that goes wrong. Fortunately his debts are bailed out by another man. That man is Raja Abdullah. In return, the Sultan appoints Raja Abdullah as chief of Klang, replacing the Sultan’s son. But the Sultan’s son also has a son. His name is Raja Mahadi. Naturally, he takes it rather personally. And I sympathise with Raja Mahadi on this matter.

- Start of Day Trip – Sentral Station, Kuala Lumpur

- Cost of Day Trip – Cheap (£)

- History Content – High

The railway line I travel on from Kuala Lumpur to Klang is the first train line the British build in Selangor. That was in 1886. Which makes this story more intriguing, as clearly, the British get entangled at some point. Thwarted by a lack of budget to traverse the River Klang, the line initially stops at Bukit Kuda, now no longer a train station. It’s only in 1901 that the train line is extended to Klang, via [1] Connaught Bridge.

Tin was mined in small quantities in Klang. When the demand for tin rises in the West, Raja Abdullah is granted permission to open tin mines in other parts of the state. Which he does in 1854, including the tin rich town of Kuala Lumpur. And so Raja Abdullah, and Klang, prosper. Raja Mahadi on the other hand dabbles in the opium trade, a perfectly legal trade at that time.

Raja Abdullah leases Klang to a British and Chinese trader. But Raja Mahadi refuses to hand any tax over to any foreigner. Plus he is more aggrieved than ever before, because on the death of his grandfather, it is his uncle who is appointed Sultan of Selangor, and not him. My arrival at the [2] Klang Railway Station still in its original colonial building, saves me from musing over exactly what tax exemption he is claiming. And just to be clear, I’m on Raja Abdullah’s side now, as one should always pay one’s taxes.

[3] Chong Kok Kopitiam, across the road from the station, does a rip-roaring breakfast trade with its Nasi Lemak and cucur udang (prawn fritters) stall. Alternatively, there’s a simple breakfast of toast, half boiled eggs and coffee served in their own brand bright yellow coffee mugs. It’s over breakfast that I learn how Raja Abdullah, a Bugis himself, refuses to punish a fellow Bugis over the murder of a member of the Sumatran ethnic community nearby. The repercussions are severe.

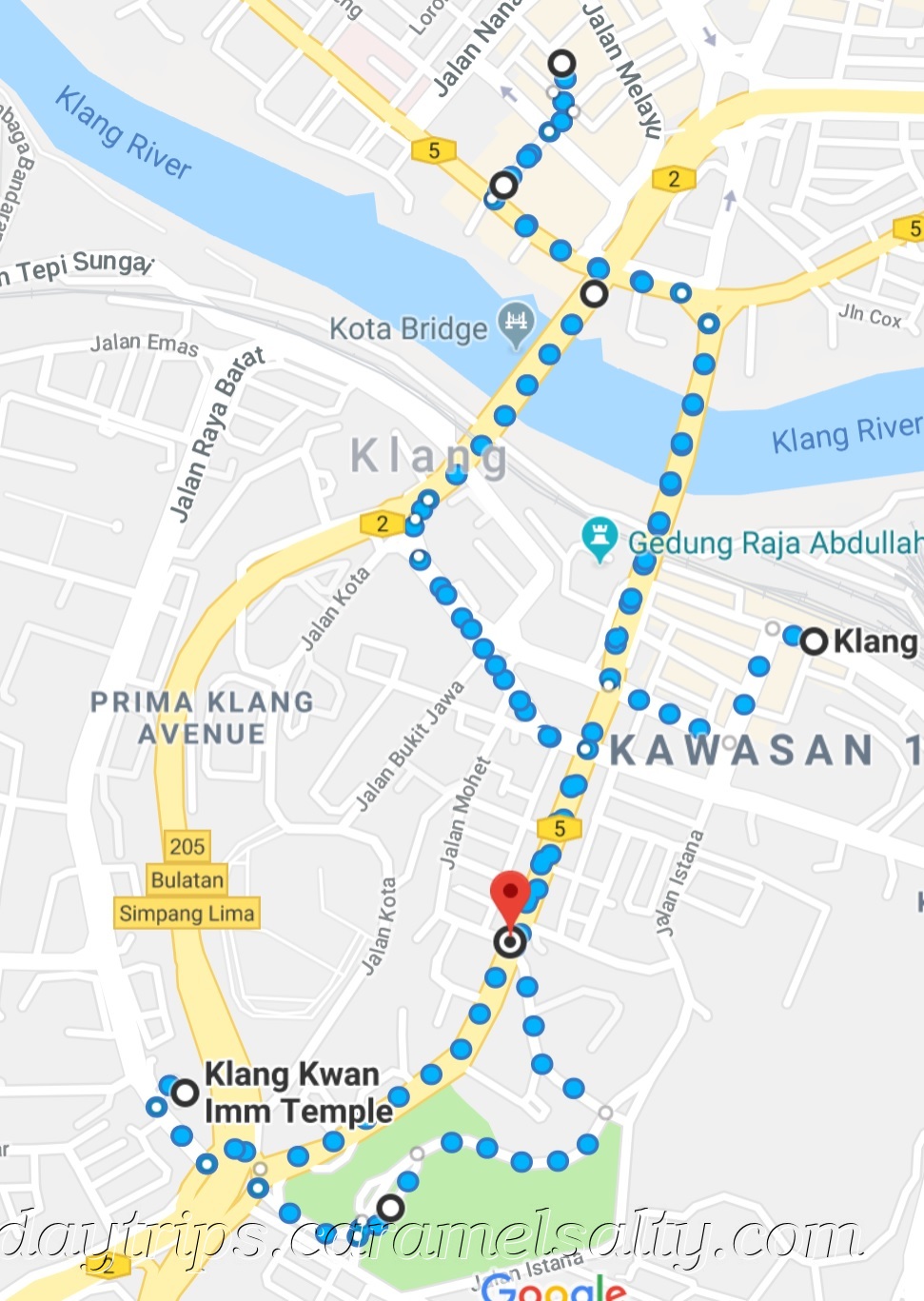

After breakfast I wander over to [4] Gedung Raja Abdullah, which when built in 1857 was Raja Abdullah’s royal residence upstairs, and a warehouse storing ammunition and tin on the ground floor. It’s now a little worse for wear and closed to the public. “Kilang” is the Malay word for warehouses, and may possibly be the origin of this city’s name. In contrast, at the end of the road I find the brightly painted red and white, still functional, colonial [5] Kota Raja Fire and Rescue Station.

I wander along [6] Jalan Dato Hamzah towards the flyover as the story continues to unfold. There had always been bad blood between the Batu Bara Sumatran ethnic group and the Bugis Malays, originally from Sulawesi. The seeds of war are planted when the Batu Bara Sumatrans inform Raja Mahadi that they are willing to support him in war against the Bugis Raja Abdullah. At this point I’m not sure whose side I’m on any longer.

And so it begins. In 1867, Raja Mahadi and the Sumatrans lay siege to the fort I am now in front of. And eventually take control of it. Some of the slain from Raja Mahadi’s side are buried inside this fort known as [7] Raja Mahadi Fort. Disappointingly, it is not open to the public. The Sultan of Selangor, alarmed by events, appoints his son-in-law Tengku Kudin to arbitrate. But when ignored by Raja Mahadi, Tengku Kudin takes side with the son of the now retired Raja Abdullah.

As I stand on this little hill fort admiring the red iron [8] Kota Bridge, the plot thickens. The Sumatrans fall out with Raja Mahadi. Something about not being given the promised land titles after winning the battle. And the murder of one of theirs by Raja Mahadi’s brother. So the Sumatrans switch sides. With the weapons that the Sumatrans bring in via Singapore, and after 6 months of bloody fighting, in 1870, the fort falls back to the hands of the other side, now led by Tengku Kudin and Raja Ismail.

Now for the British. When a pirate attack on a British ship is traced back to Raja Mahadi’s men, the British attack Kuala Selangor in 1871 where Raja Mahadi has holed himself up in after losing Klang. On gaining victory, the British hand Kuala Selangor to Tengku Kudin. However my story is interrupted by impatient hooting on the modern bridge running alongside this now redundant iron bridge. Only bikes use this old bridge. And the top deck is a tranquil pedestrianized “patio” of potted Bougainvillea.

By crossing over [8] Kota Bridge, with its views of the [9] North Klang Royal Town Mosque, I effectively bridge the gap between British colonisation and independence. When the Klang wars end in 1874, the British are effectively in charge of Selangor. Frank Swettenham is appointed the first British Advisor for Selangor. Malaysia eventually gains independence from the British in 1957. Coincidentally, that’s the same year this bridge is built.

Now I’m on the other side of the river, where I find some traditional Chinese shops. Talking about the Chinese, I realise I’ve not mentioned their involvement in these Klang Wars. So there’s more to come. Especially about how it escalates until it becomes known as the Selangor Wars. And who is on whose side. And for how long. As for me, I’m currently on the side of the British. It’s no fun being attacked by pirates.

Other Related Blogs

Klang (Part One) – A Historical Royal Town – the second part of my Klang Adventure

Tips and Suggestions

- From KL Sentral Station catch the KTM Komuter to Klang (not Port Klang). KTM Timetable from Tanjong Malim – Pelabuhan Klang is here.

- Kuala Lumpur Train Routes – map here.

- Touch and Go Cards are accepted on all trains (cashless) and buses in Kuala Lumpur. These can be purchased at LRT Customer Services Kiosks. Credit can be topped up at LRT Customer Services Kiosk and supermarket outlets (e.g. Seven-Eleven, Mynews.com) for a small charge.

- Chong Kok Kopitiam – opening times

- Watch your step. Kerbs may not exist in places, can be uneven or have exposed manholes.