Amersfoort – Where Johan, Jacob And Piet Once Lived

In 1619, a 71-year-old prominent Dutch lawyer is led to the gallows in the Hague. During his 8 months under arrest, he isn’t allowed to defend himself. A kangaroo court comprising his enemies, passes sentence. It’s an unbecoming end to a man who, in my opinion, contributed so much to the Dutch Golden Age. And it galvanises me to visit his birth town of Amersfoort.

- Start of Day: Utrecht Central Station, the Netherlands

- Cost of Day Out: Expensive (£££)

- History Content: Low

In the 11th century, there was a ford (voorde) in the river Amer. It stood at one of the few safe crossing points in the marshy expanse of the North-South traffic and the Germany-North Sea route. Whilst I don’t get to walk along that ancient track to Amersfoort, my train certainly runs close past it all the way.

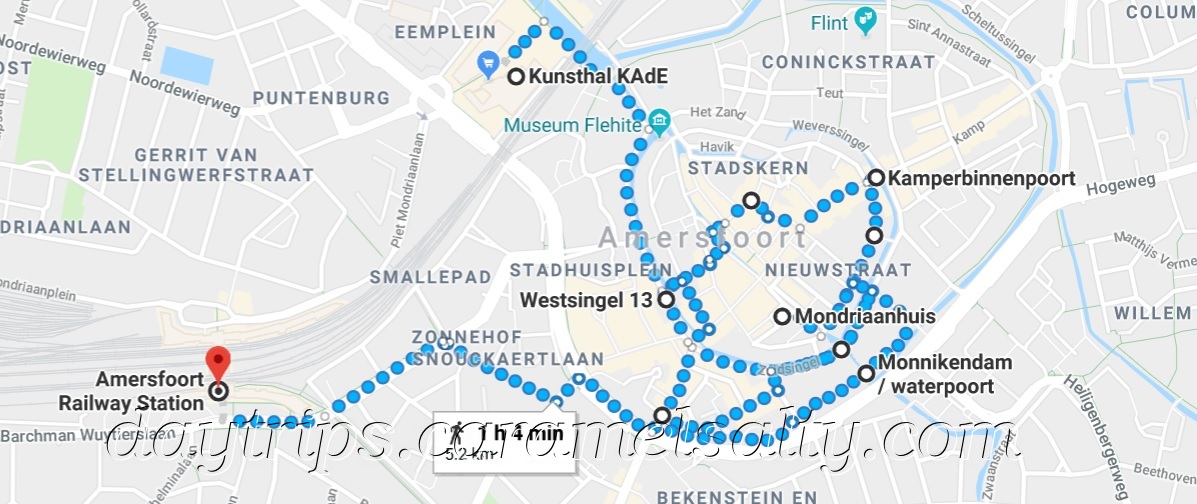

On arriving, I head down to the [1] Zuidsingel. It’s a quiet and pretty road that runs alongside a series of canals that encircle Amersfoort. Today, I’m able to enjoy the brickwork and gardens of the houses beyond. But back in 1380, a brick wall would have stood on the inner side of the canal, between me and the city.

Further along the Zuidsingel, I come upon [2] Bollenburg. A statue of a lion with a law book stands outside this abode. I’m in no doubt that this is the childhood house of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt. Born in 1547, he serves first William of Orange, and then his son, Maurice of Nassau. From his biography I can tell that he was a man of influence and strong convictions.

300 years before Oldenbarnevelt is born, Amersfoort is granted city rights. A group of wealthy weavers and cloth merchants settle and prosper in the new city. But they need protection from marauders and ambitious neighbouring dukes. Hence the first stone wall around the city is started in 1300.

The newly formed city flourishes to the point of overcrowding. The original city wall is demolished to make room. As for the bricks from the wall, they’re used to build houses along the now disused foundation. And so from the rubble, the quaint [3] Muurhuizen rises where the city walls once stood.

By 1450, a new wall consisting of 7 gates is built outside the ring of canals. One gate still standing today is [4] Monnikendam (Monk’s Dam). I have to walk through a little park where the wall once stood to climb up to the two towers which once guarded the canal entry into Amersfoort.

I retreat back to the charming Muurhuizen with its widely differing architectural styles. I love the medieval feel to this street. With age, the tall old houses lean in slightly towards the street. I wonder what secrets these clay bricks have heard spoken in the streets below.

At the quarter mark of my circumnavigation around Amersfoort, I arrive at [5] Kamperbinnenpoort. This gate, from the first set of walls, stands at the top of [6] Langestraat. As I stand facing the gate, I know that in the distance, along this olden road, lies Hamburg. Brugges is at the other end, behind me.

It’s not just traders that pass under the arches of the Kamperbinnenpoort. The Crusades also see Knights from the Holy Roman Empire (i.e modern Germany) march through Amersfoort on their way to Jerusalem. What a sight an army in armour, with the Cross prominently displayed, would have made as they make their way in to the city for rest and food, before setting off again.

As the Knights once did, I too stride along the Langestraat into the centre. But I halt in front of the Gothic spires of [6] Sint Joriskerk (St Georges), thus ending my brief reenactment of the Knight’s crusades. Sint Joriskerk is enormous. In fact it’s the largest church in the Netherlands, having once been both a church and covered market. Built in 1243, it marks the spot where that 11th century safe crossing once used to be.

Sint Joriskerk used to be covered by Biblical frescoes. This was white washed during the 16th century Protestant movement (a.k.a the Reformation). The excellent tourist leaflet points me in the direction of a painting by another famous son of Amersfoort, Jacob van Campen. The Last Judgment, 1653, was originally meant for Amsterdam City Hall, which he also designed. And up the steep, windy stone steps to the first floor, I find a room where the guild of surgeons used to meet.

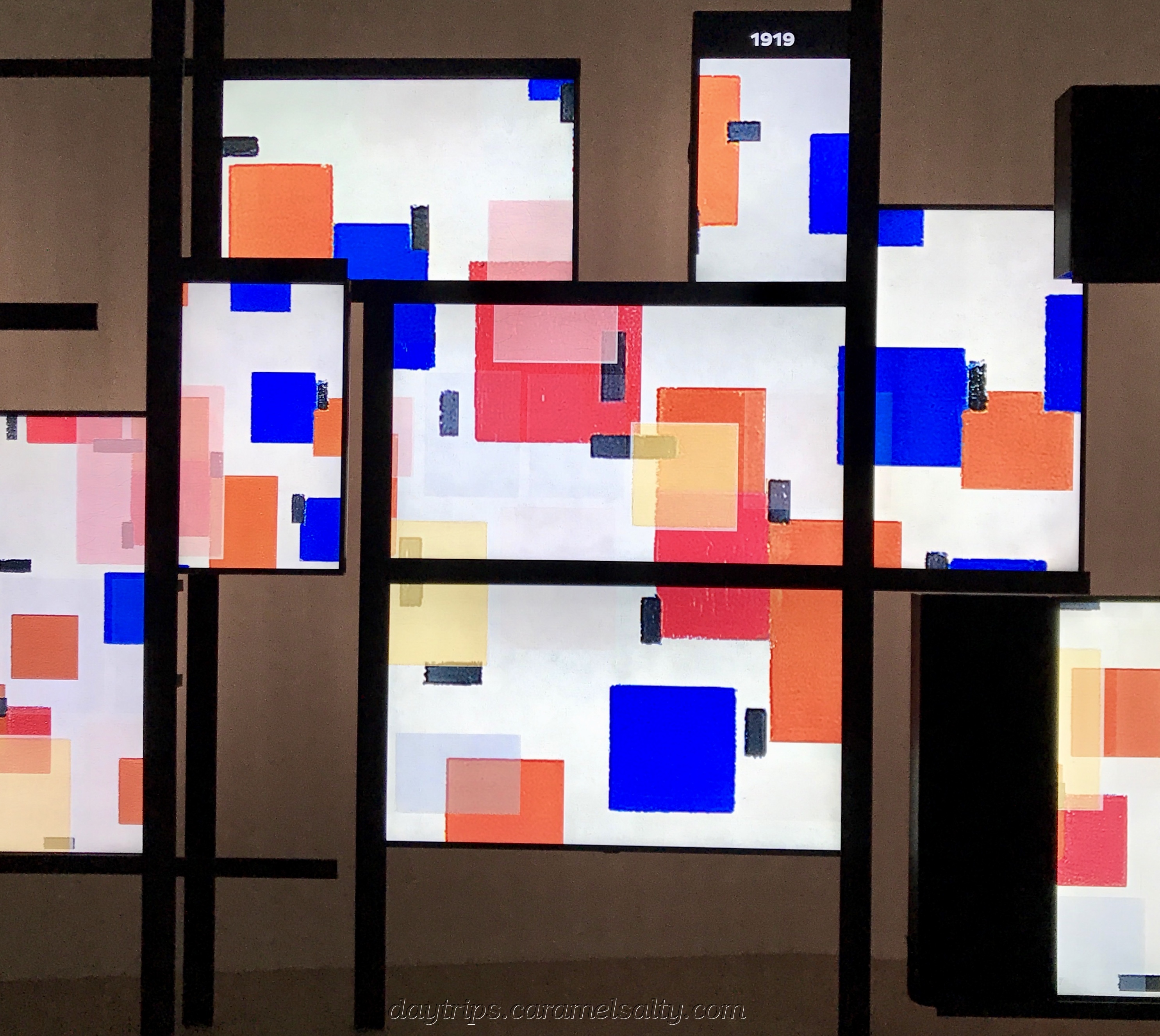

At the ripe old age of 70, Mondriaan, having fled from an invaded France, leaves a London being bombed by the Germans, for New York. It’s only when he gets to the States, that he becomes well-known. His other passion in life, dancing, is reflected in his most remembered piece.

In need of refreshments before this afternoon’s mission, I gratefully sink into the outdoor cushioned benches of [10] Brood and Zoets. There’s no need to consult my watch to remind myself of the time. I simply listen out for the 100-bell musical carillon of the Onze Lieve, just like they did before watches were invented, to know when it’s time to move on.

From my outdoor lunch seat, I can see yet another section of the Muurhuizen by Mondriaanhuis. I will head over to the Muurhuizen again after lunch. But the circular Muurhuizen reminds that it’s time to go a full circle back to the start of my story. The story of Johan van Olderbarnevelt.

Olderbarnevelt’s execution is linked to the civil war in the 1610s between the rival strands of Calvinism (Protestantism), which culminates at a gathering in Dordrecht in 1618 (see my Dordrecht blog). As he’s on the losing side, and also raises an army against a King who has backed the winning side, the King sees to it that he loses his head.

It’s the same Olderbarnevelt, who in 1602, persuades a few traders to form a trading alliance, which would eventually be known as the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VoC for short). In my opinion, it’s this well organised and well resourced organisation that spearheads the Dutch Golden Age of the 17th century.

After a morning of getting to know three of Amersfoort’s most distinguished citizens, I’m ready for my mission this afternoon to find the centre of the Netherlands, which apparently lies somewhere here. With no compass, nor a map with X marking the spot, nor a long enough measuring tape, I surprise myself by how I manage to find it this afternoon. (See my blog of my afternoon in Amersfoort)

How I Did What I Did

- Trains to Amersfoort (Netherlands Rail website) – timetable and fares available on the online journey planner

- OV Chipkaart (website) – the anonymous Chipkaart avoids queues and can be topped up by credit card at machines at all train stations. Economical if you’re doing over 20 journeys/multiple holidays

- Sint Joriskerk – May – Sep, closed Mon – Tues, Sun p.m only. Small Entrance Fee.

- Museum of Mondriaan (website) – closed Monday. Free entrance with the Museumkaart (website).